To Students Who Ask Questions

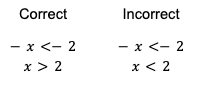

In my first year teaching, my concerns revolved more around classroom management than questions around teaching mathematics content. I figured if I happened upon a topic in my curriculum that I didn’t remember, it wouldn’t be hard to figure it out on the spot. I can successfully get the correct answer to any (high-school level) algebraic problem thrown my way, but I had never interrogated (not while I was a student, and not since becoming a teacher) why the underlying concepts of algebra worked. I don’t mean something like the steps required to solve an equation for x, but more complex, deeper questions. For example—why, when you’re solving for x (in this case, by dividing both sides by -1), do you have to flip the inequality sign (Figure 1)?

Figure 1

Example notation for dividing an inequality by -1

Sure, you have to do that to get the right answer, but why, using algebraic concepts that 9th graders have access to, do you really have to flip the inequality sign? This is a question that students ask and a step they struggle to remember every year. I found myself simply repeating “that’s how you get the answer” and “don’t forget that step!” like my own teachers had before me. Through interactions like this, I found that I knew how to do algebra. But, I didn’t know algebra.

When I started teaching algebra, I didn’t know that I had this gap between doing math and understanding math. It wasn’t until I began teaching Advanced Placement (AP) Calculus that I had to confront this idea of being able to procedurally do math vs. conceptually knowing why math works. Every class has things that make it hard to teach, but AP Calculus proved especially so. Not only was the pace break-neck, but the content was something that I had not worked with since I had taken calculus in college 10 years prior. The first year I taught it, I felt like I was re-learning calculus the entire time, and I found that I had a lot of questions about how calculus concepts worked. As with algebra, I was never truly worried that I wouldn’t be able to do the math, so I knew I could teach students how to procedurally get to a correct answer. But, I felt a large sense of unease about the fact that I didn’t confidently understand a lot of the why behind all of the interconnected pieces of calculus, and in turn wasn’t passing a rich understanding of the content along to my students.

My calculus students asked a lot of questions. I appreciated every question and leaned into them, even if I was unable to answer. For example: why does u-substitution work? Why can I rewrite an integral using a completely different function and magically get the correct antiderivative? I knew that it worked and that using u-substitution would give you the correct answer, but I didn’t feel like I had any ground on which to begin to explain to students why it worked.

In my second year of teaching AP Calculus, I started working with a Knowles Teacher Initiative coach to support my own goals for professional learning. I started out by setting a goal to “get students working in groups” because I wanted them to have richer conversations about the content of the class. As I worked with my coach and unpacked my goals for the class, I realized what I really wanted was for my students to have a more conceptual foundation of the content—this is what would drive those deeper conversations I hoped to see while they were working in groups. I wanted the same thing for myself and my students: a strong conceptual understanding of why each piece of the calculus puzzle fit together. Of course, this was a big ask—in large part because I still felt that I was lacking a strong understanding of the why of calculus.

But I realized you don’t just come to a deeper level of understanding of content without doing the work of being curious and committing to filling in the gaps.

As I began to realize that there were gaps in my understanding of calculus, I started to ask my coach about the concepts I felt unsure about. At first, I felt embarrassed that I didn’t have the answers to these questions (especially given that I was teaching students this content at the same time)! But I realized you don’t just come to a deeper level of understanding of content without doing the work of being curious and committing to filling in the gaps. We all begin our lives with zero knowledge of calculus. In order to understand it, we all must do the exact work we expect of our students: to think, to try, to question, to iterate, and to improve.

This act of questioning my knowledge and seeking a deeper understanding of mathematics was not something I had been taught to do in math class when I was a student. Even though it was something I wanted for my students, I was unfamiliar with how to do it for myself. As a student, I believed I knew calculus because I could confidently get the correct answers to problems. So as a teacher, I had to let go of my past experiences as a student and rebuild my idea of what it means to learn math. I needed to expect the same growth mindset I was trying to instill in my students for myself.

So I began to seek out questions instead of feeling overwhelmed by them. It turned out that the burning questions I had as a teacher were the same burning questions the students had—not surprising, as their questions often stemmed from me not explaining something clearly enough. I found that the topics where they would prod me were often the concepts that I felt the least knowledgeable about—places where I tried to skate by with a surface-level explanation, secretly hoping no one would question it because I didn’t understand the deeper connections of the ideas. They asked a lot of good questions, and those questions became my questions: why, truly why, does u-substitution work? Where does the chain rule come from? How can I explain to students why the derivative of ex is itself? These questions reflected the shifting nature of my class: I was fostering a curiosity about calculus for myself and my students. In teaching them to seek out the meaning behind the math, I was teaching myself the same thing.

Once I opened the floodgates to asking my coach math questions, I found myself more empowered to ask questions in any venue. I asked the other calculus teacher at my school how things worked, why he taught things the way he taught them, and if he had a good explanation for any sticking points that I had found in my lessons. I found myself watching YouTube videos about calculus—like this one from Eddie Woo (2015)—and googling things like “tabular explanation for the power rule.” I had unlocked a curiosity within myself about the content I was teaching. Googling information about the class I taught didn’t make me a weak math teacher, and it didn’t mean I didn’t know my content. It did mean that I was interested in improving my capacity to teach my content. It’s a humbling step to turn to a coworker and say “you know this thing we teach students—why does it work?”

This kind of vulnerability is hard to tap into. And even as I was opening these doors within myself to allow for questioning, I would repeatedly find my coworkers were not all at the same place on this journey. I remember an interaction with a coworker when they joined the calculus teaching team: I had offered that if they ever had questions about the content, I would be open to chatting because I love talking about calculus. I realized I had hit a sore spot with this coworker when they cut me off and briskly responded “I know calculus.” I hadn’t meant to imply that they didn’t know calculus, I had just meant that I was hoping to have the same open dialogue I had started with my coach—where we could dig into the difficult content-based questions we still, as teachers, were grappling with. I believe I could teach calculus for 30 years and still have questions about why or how or what would be a better way to explain or demonstrate relationships between concepts. That’s what makes it exciting! And it’s more fun to do this sort of exploration and dialogue with others.

I’ve continued teaching Algebra 1 and AP Calculus, and while I was working to make my calculus class more conceptual and inquiry-driven, I never considered whether the same approach could apply to Algebra 1. I had fallen into a trap that I saw many math teachers fall into: calculus is “worthy” of this sort of exploration as a teacher because we acknowledge that it is a difficult subject that is hard to explain to students. There is no way over the course of the year that I can comprehensively explain every single piece of content assessed on the AP test (this is why you only need to score a 60% on the exam to receive the top score of a 5). It’s also safer to admit as a teacher of an AP course that you have questions about the content, but it’s much, much harder to turn to a colleague and admit that you are curious about some of the conceptual underpinnings of algebra. No one will argue with you that there are rich, conceptual questions to explore in AP Calculus, but is the same not true for Algebra 1? This question arose at the end of last year, when I finally felt like I had the bandwidth to move away from my massive overhaul of AP Calculus.

It was naive of me to think that Algebra 1 was “easy.” All of the richness of explaining things conceptually to students that is so evidently necessary in calculus is also present in algebra—perhaps more so, as the procedural content is small (just a few steps to solve each problem), but the why behind those steps is so fundamental. I was shocked to realize that almost none of the content in my Algebra 1 class had a conceptual foundation. My class typically looked like: do this step, then do this step, then you have your answer. Why? Because that’s how you get the right answer. It seemed that there was no room for a conceptual focus for the class because I saw students struggle so much with the procedure that, in the (paraphrased) words of the algebra team at my school: “there’s no time to focus on concepts when we have to get through so much procedural content and it takes so long to get through the procedural content because the students struggle so much with it.” I no longer believe this to be true. I think conceptual understanding is foundational for students to understand why they do the procedure. Part of why students struggle is because they don’t understand the reasoning behind the method. Sure, some students struggle with algebraic fluency, but they mostly have difficulty memorizing a dozen seemingly random steps of algebraic manipulation.

So along the way, I had picked up all the tools to do the math without wondering or caring about the why.

I think the concepts in algebra are harder to explain to students because I, like many math teachers, found math to be a breeze in school. I picked up all the procedures (the steps to getting an answer right) without ever interrogating the underlying concepts that made those procedures work. So along the way, I had picked up all the tools to do the math without wondering or caring about the why. Much of what underlies algebraic reasoning has to do with arithmetic, a core development of elementary school math. These early years of math education are foundational knowledge that high school teachers don’t have access to because we don’t learn how to teach students math (or think about math) the same way the students have been taught in their formative years.

Let’s return to my previous example about solving for x (and dividing both sides by -1), as shown in Figure 1. To understand why you “flip the inequality” you have to really understand how numbers work—something that you learn in elementary school—because you have to understand that multiplying or dividing a negative number by a negative number will make the result a positive number.

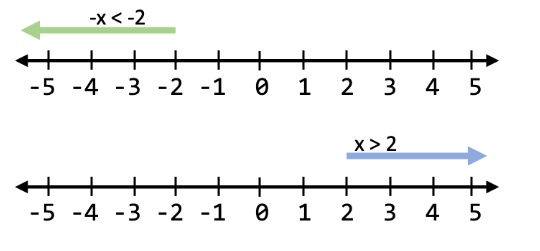

This concept of “flipping the inequality” can be seen on a number line, where you can see that when you divide by -1, the numbers change from negative to positive, and the order of the numbers reflects (or flips!) across 0. All of a sudden, the numbers that were “less than” while negative are now “greater than” while positive. For example, 5 is a solution for x, because -5 is less than -2 but 5 is greater than 2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Number line visual of dividing an inequality by -1

I model what it looks like to be in the middle of learning something, because we never arrive at the “end” of learning.

This is just one of many topics in algebra where I didn’t fully understand the concept until I dug into students’ confusion and explored my own questions about it. I hope to spend the rest of my career unpacking these nuances of algebra and finding the right ways to explain them to my students.

We say “no dumb questions” for a reason—there is richness to be found when I really listen to students’ questions. I’ve learned that the questions my students have are valid and worth exploring, and they may be asking them because they’re missing something that’s getting in the way of real understanding. I consider their questions lamps that shine a light on places where my own understanding might not be as rich as it could be.

I’ve learned that it is okay as a teacher to not have all the answers, but what is important is what I do when I realize I don’t. I model what it looks like to be in the middle of learning something, because we never arrive at the “end” of learning. When I come across ideas I don’t fully understand, I feel charged with asking my coworkers, going to Google, even talking ideas through with students (I once read this article aloud to students in my class and we all learned this derivation of volume together (Chamberlain, 2025)). When I find a place where I have a gap in knowledge, I know that improving my understanding will improve my ability to teach math.

There’s a joke that on the first day of school, math teachers will say, in a panic, “we’re already behind schedule!” I was nervous to move my AP Calculus class from a procedural to a conceptual approach because we truly do not have enough time to cover all of the curriculum. But it turns out that conceptual understanding is a richer way of learning content. There is a study that shows that if students understand less content, but more deeply, they will do better on standardized tests (Arrington, 2009). And my AP scores reflected this: my scores after I moved to a conceptual understanding of content had a marked improvement over my scores where I had emphasized a procedural approach. The time we spend on this: on our own, improving our understanding of content, and in our curriculum, making the content more meaningful for students, has a direct benefit to our students. As teachers, we are human, and we don’t have all the answers. We are charged with demonstrating the same growth mindset that we expect of our students—we too can be learners, and our classes can reflect that. And as we grow, so will our students.

Citation

Zorn, L. (2026). To students who ask questions. Kaleidoscope: Educator Voices and Perspectives, 12(2), https://knowlesteachers.org/resource/to-students-who-ask-questions.